shutterstock_1456257662.jpg

A new IIEP-UNESCO Working Paper tackles the growing issue of fragmented and hard-to-navigate higher education systems.

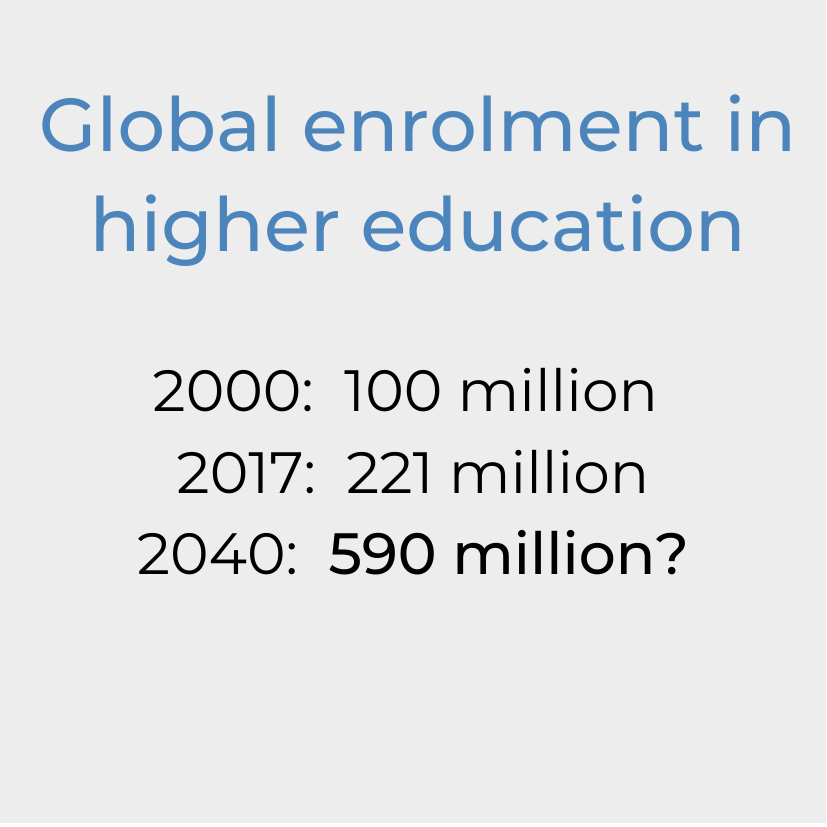

Higher education has never been more in demand, and the global population enrolled in higher education has never been more diverse. A random sample of higher education students might now include (alongside ‘traditional’ learners) part-time learners, older adults returning to education, international students, and migrants, all with different goals and challenges. How can higher education systems keep up with this ever-increasing expansion and diversification?

The good news, as laid out in IIEP’s latest Working Paper, is that many countries are adapting to the changing shape of higher education: institutions and other providers now differ widely with regard to their status, origin, mission, access routes, types of programmes, and modes of delivery. However, this means that systems as a whole are becoming ever more fragmented. Michaela Martin, Programme Specialist at IIEP and a co-author of the paper, says that students today ‘find it more difficult to understand the increased complexity of the higher education offer.’ There are many stakeholders involved at the national, institutional, and individual levels, and it is vital that policy frameworks, instruments, and targeted measures align with each other.

Higher education for a more prosperous planet

Where once higher education was restricted to a small minority, it ‘has evolved from providing education for a few elite groups to developing the knowledge and raising the qualifications of the broader population’. A more educated workforce can fuel social and economic development, thus helping countries become more competitive in the global market, and in turn improving the lives and prospects of individuals.

Education 2030 encourages countries to develop well-integrated education systems that allow for entry and re-entry at all ages and all educational levels, stronger linkages between formal and non-formal structures, and recognition, validation, and accreditation of knowledge and skills acquired through non-formal and informal education. |

The global education community also recognizes higher education as a key driver for the attainment of SDG 4. It follows that flexible learning pathways will form a key part of any inclusive, high-quality, equitable system that truly promotes lifelong learning for all.

Countries’ higher education provision must be well articulated if students are to enter, progress through, and complete the level of study they need to meet their professional and personal objectives. A well-integrated system, where flexible learning pathways are in place and, crucially, known and accessible to those who need them, is likely to be more equitable and inclusive, more effective in fulfilling its mission, more financially and operationally efficient, and more equipped to serve the needs of its society.

Planning for flexible learning pathways

To explore the implementation, effectiveness, and impact of flexible learning provision in higher education, IIEP recently launched a research project that will include an international survey and a series of in-depth country case studies.

As part of this, IIEP has now launched a new Working Paper on the subject, entitled SDG 4 – Policies for Flexible Learning Pathways in Higher Education: Taking Stock of Good Practices Internationally. Co-author Michaela Martin explains that ‘in many contexts flexible learning pathways are not yet a national priority for higher education. Even if they appear to be an objective of higher education policies, they are not necessarily accompanied by supportive instruments and targeted measures to facilitate their implementation.' This new study shows possible routes forward for planners and policy-makers looking to better integrate the entirety of their higher education offer.

After laying out the key concepts and definitions (such as ‘transfer’, permeability’, and ‘articulation’), the authors identify potential obstacles to the implementation of flexible learning pathways. The paper then highlights policy frameworks and instruments that have been successful in various contexts, for example quality assurance, credit accumulation, and guidance services for students. Finally, it sets out a number of targeted measures that might serve as ‘good practices’ for policy-makers in other countries.

Drawing on examples from countries worldwide, the Working Paper illustrates practical approaches to developing flexible learning pathways in higher education. The authors discuss, among many others, Jamaica’s proposed integrated higher education system, the national qualifications frameworks in South Africa and Malaysia, the recording of non-formal education in the Republic of Korea, and the recognition of online learning (MOOCs) in India and the Netherlands.

To find out more, download the Working Paper for free from IIEP’s publications website.

| To stay informed, subscribe to IIEP-UNESCO e-newsletter or follow us on LinkedIn, Twitter, and Facebook. |